Bulletin for July 6, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinBulletin for June 29, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinUpdates from the 45th General Assembly

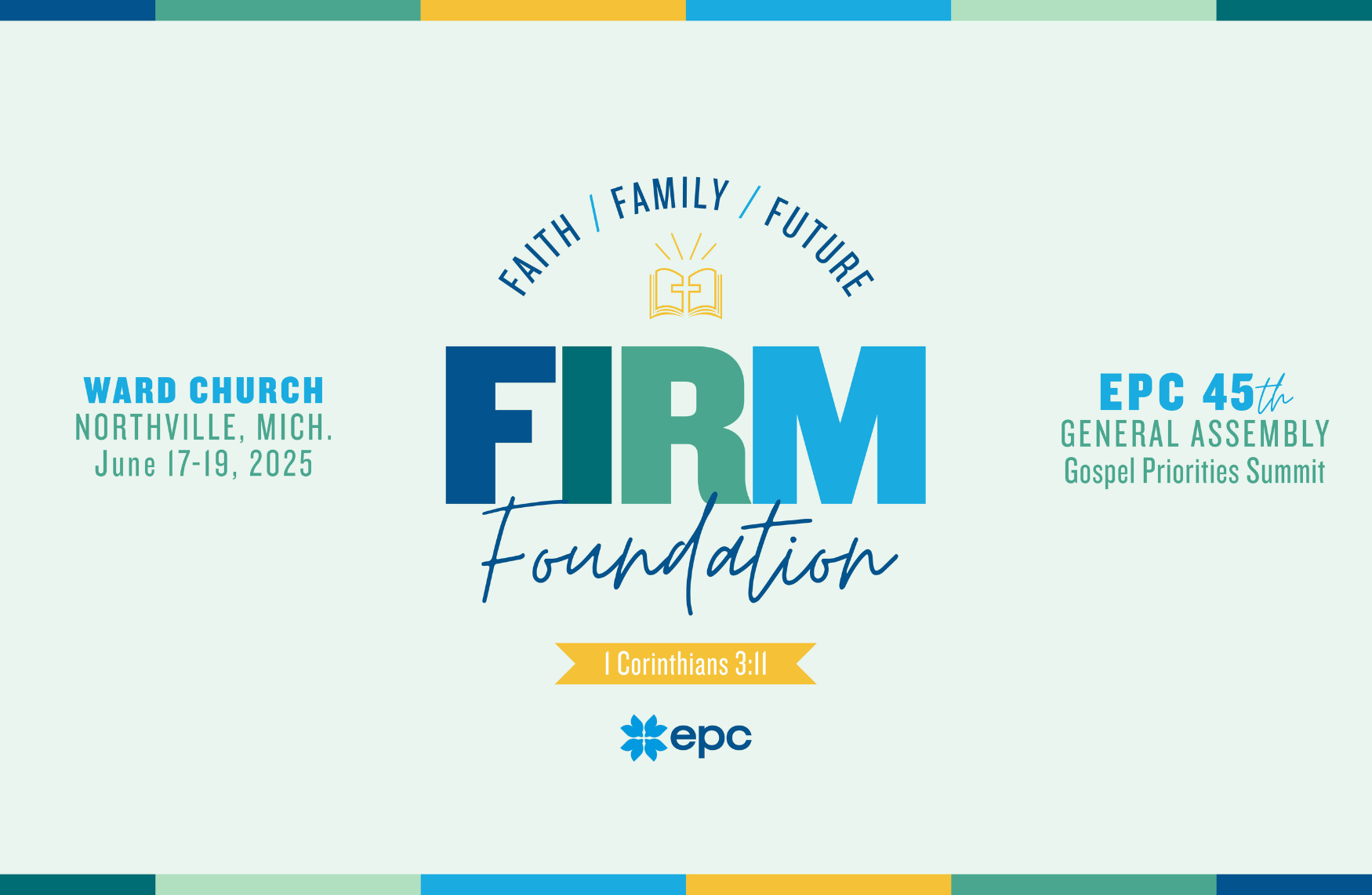

Outgoing moderator Victor Jones’ exhortation during Thursday worship.The 45th General Assembly of the EPC met at Ward Church in Detroit, MI, on June 17-19. If last year’s assembly was a little more raucous than usual, this assembly was a return to normalcy. We still dealt with some important issues, but the temperature of the room was much lower than it was at times in Memphis. Here are a few things I want to make note of.

Ordination Standards

After two years of work, the Ad-Interim Committee on Ordination Standards brought sixteen (!) recommendations to the floor concerning the ordination process. These represent an extensive revision of several areas of the Book of Order. We only barely touched ordination standards; the committee requested another year to work on those. These recommendations mostly dealt with clarifying a process and codifying things that were previously customary, but not required.

Two of the more substantive actions we took pertained to educational requirements. First, we removed the requirement for a bachelor’s degree. We still require a seminary degree or its education equivalent for ordination, but there are ways to obtain this education without a bachelor’s degree. Second, we removed the “extraordinary clause.” This was essentially a nuclear button to waive all educational requirements for ordination and was probably used too frequently. Now, every candidate in the EPC will be held to the same educational standard.

Most of these actions will require ratification by the presbyteries and next year’s GA to take effect.

SSA and Ordination

A little background on this: there is a single church that left the PCA a couple of years ago whose pastor has, at a minimum, concerning views on homosexuality. The church and pastor have sought to be admitted into the EPC. In response, several overtures were sent up to last year’s 44th GA. The presbytery that would receive this church sent up an overture seeking advice from the GA on how to handle the situation, and several other presbyteries (including our Gulf South Presbytery) sent up related overtures. As a result, at last year’s GA, all of those overtures were answered by the formation of an ad-interim (which simply means temporary) committee to study the issue and provide recommendations to clarify our Book of Government and our position papers and pastoral letters on human sexuality. There was also an agreement that no court of the church would take action on any matter pertaining to this issue until the committee finished its work.

This year, we received a preliminary report and draft proposals from that committee. You can read these on the EPC website. As I did, you will likely find things you like and things you don’t like in these documents. Keep in mind these are drafts that will be edited based on feedback prior to their formal recommendation at next year’s GA.

On Wednesday at GA, we had a feedback session with the committee to discuss their drafts. Many elders voiced concern about the use of the term “gay Christian” in one of the documents. The committee indicated their reception of that criticism, and I expect them to make favorable edits. There were other concerns about language and clarity, but I got the sense that we were really working on doctrinal precision and pastoral wisdom.

The EPC’s position on homosexuality is clear: homosexual acts and desires are sinful and require repentance, and there is a Christian duty to flee from all temptation, including homosexual temptation. The question now is largely about ordination and what we expect of candidates and ministers with respect to our clear ethical affirmations. The analogy I used last year still holds. We have drawn a clear line in the sand on homosexuality, and the question now is what kind of fence we want to put on that line. Of course, I could be surprised next year, and things could go sideways. But overall, I’m optimistic that we are heading in the right direction.

PC(USA) Missions

As some of you may know, the PC(USA) recently shut down all of their mission activity and fired all of their missionaries. In response, New River Presbytery sent up an overture requesting that the PC(USA) release funds specifically designated for missions to the EPC. The rationale was simply that many faithful people had given monies for that purpose over the years, including current members of many EPC congregations, so that it would be worth at least asking. I voted in favor of this overture, but it narrowly failed for a variety of reasons. Some were concerned about getting entangled in a legal relationship with a very litigious denomination, others pointed out that we didn’t really know what we were asking for or if there was even any money left, and even others were concerned about how this would affect a number of faithful churches seeking to exit the PC(USA). But no matter which way the vote went, I think it does give us a little insight into the EPC’s relationship to the PC(USA). It would be worth watching the debate on this overture if that relationship is something that interests you.

EPC World Outreach

Perhaps the highlight of every GA is the work the EPC does in missions. We commissioned a number of new missionaries this year to go to some of the most difficult and least Christian places in the world. For the vast majority of them, their identities are protected because they are truly placing their lives on the line for the sake of the gospel. They even take vows to accept the risk of martyrdom. This is no vacation, but a serious calling from God. Pray for these missionaries as you are able. It’s the most important thing you can do to support them. You can find out more at epcwo.org.

Your friend in Christ,

Reid

Bulletin for June 22, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinBulletin for June 15, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinGeneral Assembly

This week, the 45th General Assembly of the EPC meets in Detroit, Michigan. I’ll be leaving on Monday to represent our church and presbytery as a commissioner. This is an important meeting, and we’ll be addressing a variety of issues. If you’re interested you can visit epconnect.org/ga2025 to see all the details. All assembly business will be livestreamed. Feel free to jump onto the livestream at any point to see some of the things we’re doing. I’ll give a brief report when I return home, but if you have any questions about GA, let me know, and I’ll do my best to answer them. Most importantly, be in prayer for me and all the commissioners as we seek to discern and represent the mind of Christ to the EPC family.

Your friend in Christ,

Reid

Bulletin for June 8, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinUpdates

-

The Lord’s Supper will be served this week. Please be in preparation.

-

Choir and Prayer Meeting will not meet during the month of June.

Bulletin for June 1, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinBulletin for May 25, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinUpdates

-

Communion is scheduled for Sunday, June 8. Please be in preparation over the coming days.

-

I will be on vacation next week, so there will be no choir or prayer meeting. We’ll also take the week off from elder training.

Your friend in Christ,

Reid

Bulletin for May 18, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinChrist the King

We’re back to looking at the Shorter Catechism, and we continue with the kingly office of Christ.

Q. 26. How doth Christ execute the office of a king?

A. Christ executeth the office of a king, in subduing us to himself, in ruling and defending us, and in restraining and conquering all his and our enemies.

Notice that the Catechism lists four ways Christ executes the office of a king.

First, for any king to be a true king, he must have subjects. I can declare myself king of Greene County, but if no one follows me or recognizes my kingship, then that declaration doesn’t mean much. So Christ’s first duty as king is to subdue a people to himself, and he does this by applying the gospel to us. In John 17, Jesus prays,

Father, the hour has come; glorify your Son that the Son may glorify you, since you have given him authority over all flesh, to give eternal life to all whom you have given him.

The kingly authority of Christ comes from the Father who has given him the power, through the Holy Spirit, to make people Christian so that he would have a people to rule.

Second, having subdued a people to himself, he rules them. This is especially relevant given that the Roman communion has just elected a new Pope whom they claim to be the ruler of the Church on earth. But we believe the only head of the Church is Jesus Christ, and he rules us through Word and sacrament. This is at the heart of the Great Commission:

And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

Notice that Jesus starts with his authority before telling the disciples what to do. In other words, he says, “Since I am your King, take my royal decree (the Word) and royal seals (the sacraments), and use them to guide you.”

Third, Christ defends his people. Of course, he defends us in all sorts of ways, but the primary way is to keep us secure in salvation. He says in John 10:

I give them eternal life, and they will never perish, and no one will snatch them out of my hand.

Once we have entered into Christ’s kingdom by faith, we are secure inside the heavenly gates because Christ protects us from all who would seek to snatch us away.

Finally, he restrains and conquers all his and our enemies. Jesus is not a pacifist. Notice what Psalm 2 says:

The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD and against his Anointed, saying, “Let us burst their bonds apart and cast away their cords from us.”

Here we have a picture of God’s enemies rising against his Anointed (lit. “Messiah”), but they are not free, they are already restrained. There they remain, restrained, until they are finally conquered, which is what the death of Christ begins. At the cross, Jesus triumphed over, conquered, his enemies (Colossians 2:15), and now ascended to the right hand of the Father, he reigns until the day when all those enemies will be finally crushed under their just condemnation.

Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. (1 Corinthians 15:24-26)

Is Christ your King? Have you bowed the knee to his rule? Do you receive his kingly promises in Word and sacrament? If so, then rest secure: your King sits at the right hand of the Father, interceding for you—and one day, he will free you from all who rise against you.

A Note on Galatians 3:19

In this week’s sermon text, Paul throws in an odd little note about how the law was given through angels. Paul’s not the only one in the New Testament who mentions this; Stephen also talks about it in his speech. If you read the Exodus story, this is not something that immediately jumps out at you. In fact, it seems as if God is speaking directly, and we even read that he wrote the Ten Commandments on the stone tablets with his own finger. So how do we reconcile these things?

There are a couple different answers, but this is the most common and, in my opinion, most satisfying. If we begin to reflect on the nature of God, we remember that “God is a Spirit, and has not a body like men.” This means that God does not have vocals cords and hands to speak or write.1 In recognition of that fact, most commentators going all the way back even before Christ understand these things to be the result of angelic forces. Since God does not have a body to form speech, his servants, the angels, formed the words for him. The same is true of God’s writing on the stone tablets. In fact, if you compare the description of fire and thunder at Mount Sinai to the descriptions of angels in the prophetic books, it’s clear that these are not natural phenomena at Sinai, but the angels themselves.

This is what Paul and Stephen mean when they say the law was given “through angels.” The angels are the means by which God gave the law to Moses. In effect, since God does not have a body like men, the angels themselves function as his body so that he is able to audibly and visually express himself on earth.

Your friend in Christ,

Reid

-

Of course, the Son has a body, but only according to his human nature. In other words, the person of Christ has two natures, human and divine, but the attributes of each aren’t communicated to the other. ↩︎

Bulletin for May 11, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinBulletin for May 4, 2025

Download Sunday’s BulletinPsalm 23

This month, we’ll be learning Psalm 23. We’ve sung this a couple of times to the tune of Amazing Grace, but this week, we’ll start singing the tune written for it. Listen here to get ready to worship on Sunday.

Presbytery Update

I would normally write my own update for presbytery, but our Stated Clerk, John Carter, has started putting together a newsletter for each meeting that I’m going to share with you. I hope you’ll find it encouraging.

Presbytery NewsletterYour friend in Christ,

Reid